An innovative path to true holistic health and the massive leap we need to heal

Bad grades

Herman Hollerith, the child of German immigrants born in the 1860s, once famously jumped out of a window to avoid schoolwork. He hated school so much he eventually left the New York City school system entirely.

Hollerith went on to work in the U.S. Census Office. The main problem of the era was the laborious process of manually counting the responses. The process was so slow that by the time the 1880 census was fully counted, it was already time to launch the 1890 census.

Hollerith, never a rule-follower, responded to the problem by creating a tabulation machine using punch cards (think index cards with holes in them). This remarkable invention completed the census count two years ahead of schedule and led to the founding of the Computer-Tabulating-Recording Company, the predecessor of today’s IBM.

AI eats the world

Compared to the early, punch-card-driven mechanical engines of the 1800s, computers today are formidable and intelligent. Alan Turing, the father of theoretical computer science and artificial intelligence, enabled the Allies to defeat the Axis powers in World War II through his decryption machines. His Imitation Game propelled the development of smarter and smarter computers that could fool people into thinking they were talking to another human.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming our lives, from virtual assistants such as Alexa, Siri, and Google Assistant to facial recognition systems. Now, ChatGPT can even pass a range of human educational tests, ranging from high school history quizzes to US medical board examinations.

But this article isn’t really about the history of artificial intelligence. It’s about healthcare (surprise!).

It’s about power

The connection lies in understanding the power of computation. This is essentially how quickly a computer can “think”. The greater its computing power, the faster a task can be completed. Thinking by a computer is, in many ways, similar to thinking by a human. This is especially evident in the evolution of neural networks and deep learning, which are subsets of machine learning and thus AI. Similarly to a human brain lacking sleep and nutrition, an artificial brain without adequate power will be as impressive as a clunky Roomba.

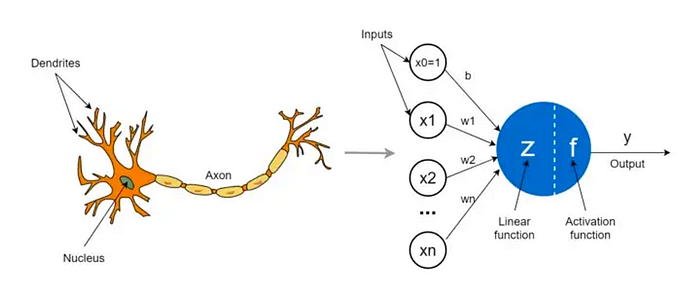

Let’s take a step back. What are the components of a computer that do the thinking? Artificial neural networks (ANNs), which were named for their resemblance to biological networks, can be broken down to their simplest component: the perceptron (also known as the neuron). The artificial neuron is a mathematical function, but it can be thought of similarly to a biological neuron. It takes in inputs and produces outputs.

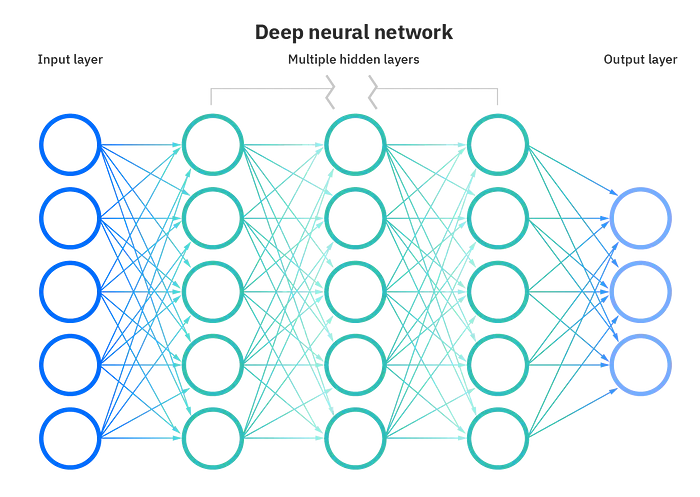

“Non-deep” machine learning uses a single layer of neurons for processing. If we were limited to this form of ML, we wouldn’t have the powerful speech recognition algorithms used in modern transcription tools, let alone the impressive natural language processing solutions like ChatGPT and DALL-E.

What’s the deal with deep learning?

Deep learning is “deep” because it has more than one layer of neurons between the input and the output. These hidden layers add immense complexity to a model, leading to game-changing results.

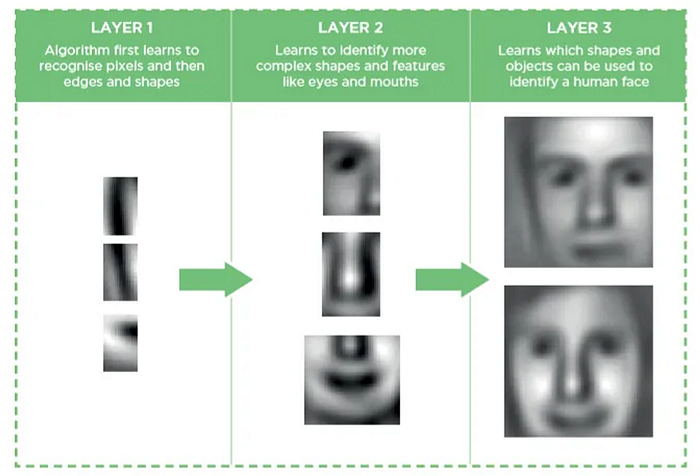

The more hidden layers, the more powerful the network due to efficiency of the computation being done. This is what allows a computer to recognize a human face rather than just describe lines and shapes.

Deep learning shines for large data volume problems, which is what brings us to the healthcare analogy.

Deep Healthcare

If input is a patient’s illness and output is a patient’s intervention, you can imagine a single neuronal node being a doctor.

However, we can’t rely on a single layer of nodes. Can you imagine a frontline made of only doctors, juggling the infinite demands of the healthcare system? We’d fall apart even more than we have in the current system.

Instead, in healthcare, each doctor “node” may consult with other doctors in the same layer, or with staff such as nurses and medical assistants in additional layers of nodes.

More nodes, no problem, right? It turns out, absolutely not. Our medical system solves problems by throwing more money and humans at them, but this is incredibly inefficient. It leads to more errors and ultimately suffering for both patients and doctors alike.

The main issue in healthcare is that all these additional human nodes and layers are connected via broken communication systems. Think of pagers and fax machines (which are still used in hospitals) or clinician messaging portals blocked by multiple passwords. Even human speech and plain writing can be faulty; my main medical school research project was centered around the different names oncologists and pathologists used to describe a single type of cancer (more than 11, it turns out).

The more human nodes in healthcare, the more disagreements, miscommunications, and inefficiencies. For example, health insurance agents and doctors may argue over prior authorizations, or a nurse practitioner may misunderstand a supervising physician’s clinical protocol. This is why we have bloated electronic medical records (EMRs) and practitioners becoming burnt out and even leaving their careers. Just last month, NYC faced a major crisis with 7000+ nurses striking due to conditions caused by underresourced staff.

Thus the need for deep healthcare, which equates to higher efficiency, higher quality healthcare. To maximize efficiency, it is essential to reduce the number of human layers and strengthen the remaining ones with well-designed machine layers. We do need more nodes, but technology nodes, not human ones. This could mean technology-based automations, AI interpretation and output layers, clinician assistance software, or patient coordination technologies. This allows for improvement in analysis, understanding, and decision-making as well as solidification of communication when it is needed between humans.

We also do not know what we do not know, so it is important to incorporate a set of checks and balances with “humans-in-the-loop” at every step to guarantee quality and ethical standards are met.

Our mission at Curio to elevate health services is paired equally with our investments in technology and clinical processes. We’re working toward efficient and effective clinical interventions with deep healthcare to achieve better outcomes without nearly so much human and financial cost. We use best practices and evidence as published in peer-reviewed literature to create our initial designs. But then we also follow the scientific method and have incorporated a cycle of constant feedback. Thus the system we’ve created is a living system. This is a concept I will dive into at a future point, because it’s done so poorly right now in healthcare. We need healthcare workers who are on the front line to be adept at understanding technology design and innovation, and vice versa.

Deep vs. Comprehensive vs. Holistic Healthcare

One of my co-founders and our CTO Matteo originally suggested that “deep healthcare” be the opposite of “shallow or superficial healthcare”, which also makes a lot of sense. But my partner, who helped me proofread my first draft, said this version as written is a good explanation so we’re going with it (recognizing that he is absolutely biased — I bought groceries this week, plus he’s an AI scientist). In any case, I am open to any reader’s feedback; like our systems at Curio, I am constantly listening and evolving!

Every patient wishes they were treated as a whole person, not just a disease. Which is why it is mind-boggling to me that so many healthtech companies today are serving the opposite cause. We now have hundreds of brands that reduce doctors to button-clicking prescribers for ED, hair loss, and acne. My theory on the subject is that patients are simply too frustrated with how they’ve been treated by the healthcare system and have chosen to take their care into their own hands with the help of Google (or ChatGPT now). They then demand the fastest way to the pill of their choosing. Doctors are compliant with this because it’s how we get paid — prescribing a pill is easy and billable, after all.

But imagine a world where we actually solved our deeper physical and emotional ails. One where we had healthcare which accounted for the reasons why we might suffer symptoms of ED or fatigue. We’d be a world of people with a lot more happiness and a lot fewer drugs, for one.

That is a world which has comprehensive, holistic healthcare. One which is possible only with deep healthcare.

“Deep” may sound similar to “Comprehensive” or “Holistic” in reference to healthcare. But all three concepts are different, as I’ll explain below.

Comprehensive healthcare can roughly be understood not only traditional medical interventions like chemotherapy for cancers, but also preventive care like mammograms for breast cancer detection, and rehabilitation such as physical therapy after a hip replacement. Comprehensive healthcare covers a wide range of medical services and specialties under a single roof (physically or virtually). Real-life examples of comprehensive healthcare are mostly giant healthcare systems which include everything from surgical suites to primary care offices.

Holistic healthcare, on the other hand, is a description of the whole-person approach. Rather than focusing solely on the physical symptoms of a patient’s condition, holistic healthcare looks at the overall health of the patient, including physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being. This approach looks at the patient’s entire lifestyle and environment, as well as their physical health, in order to provide a more complete picture of their health and the best way to treat it. Unfortunately, holistic medicine is more theory than reality in most of American healthcare, but there are some (relatively) small efforts in existing clinics and systems.

We (at Curio) are also dedicated to more comprehensive AND more holistic healthcare. But I wrote this article for deep healthcare because, without effective and efficient processes, we could never even dream of achieving comprehensive or holistic healthcare.

Going back to the computers analogy. When we had Hollerith’s punch-card computer, we managed to count census results much faster before, but it still took years. It also required many human operators to function. It doesn’t take much understanding of computer science to recognize that such a computer couldn’t solve your calculus homework in a timely manner, much less understand and take into consideration a patient’s family context when they present to a doctor’s office.

Now that compute power has reached its modern levels, we can find the quickest way home and create beautiful music and art with computers in our pocket. Similarly, it is only when we have augmented the medical system to be true, deep healthcare will we be able to achieve actual comprehensive and holistic healthcare.

***

Hillary Lin, MD is Co-founder and CEO of Curio — Psychedelic technology and clinical services for healthcare. Dr. Lin is a Stanford-trained, board-certified physician with research and clinical interests in neuroscience, mental health, and oncology. Read more of her and Curio’s publications by signing up at http://joincurio.com/newsletter.

***

References

Aul, W. R. (1972, November). Herman Hollerith. IBM Archives: Herman Hollerith. Retrieved January 30, 2023, from https://www.ibm.com/ibm/history/exhibits/builders/builders_hollerith.html

Wikimedia Foundation. (2023, January 21). Alan Turing. Wikipedia. Retrieved January 31, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Turing

Wikimedia Foundation. (2023, January 15). The imitation game. Wikipedia. Retrieved January 31, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Imitation_Game

Wilde, J. (2023, January 26). CHATGPT passes medical, law, and business exams. Morning Brew. Retrieved January 31, 2023, from https://www.morningbrew.com/daily/stories/2023/01/26/chatgpt-passes-medical-law-business-exams

Strickland, J. (2010, March 29). What is computing power? HowStuffWorks. Retrieved January 31, 2023, from https://computer.howstuffworks.com/computing-power.htm

Wikimedia Foundation. (2023, January 22). Perceptron. Wikipedia. Retrieved January 31, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perceptron

Kavlakoglu, E. (2020, May 27). AI vs. Machine Learning vs. Deep Learning vs. neural networks: What’s the difference? IBM. Retrieved January 31, 2023, from https://www.ibm.com/cloud/blog/ai-vs-machine-learning-vs-deep-learning-vs-neural-networks

Mahapatra, S. (2019, January 22). Why deep learning over traditional machine learning? Medium. Retrieved January 31, 2023, from https://towardsdatascience.com/why-deep-learning-is-needed-over-traditional-machine-learning-1b6a99177063

Hillary Lin, M. D. (2023, January 17). We are overmedicated. Medium. Retrieved February 1, 2023, from https://medium.com/joincurio/overmedicated-psychedelics-healthcare-systems-change-8be289d34d74

Otterman, S., Goldstein, J., & Gross, J. (2023, January 12). Nurses’ strike ends in New York City after hospitals agree to add nurses. The New York Times. Retrieved February 1, 2023, from https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/12/nyregion/nurses-strike-ends-nyc.html

Wikimedia Foundation. (2023, January 29). Biopsychosocial Model. Wikipedia. Retrieved February 1, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biopsychosocial_model

.jpg)

.jpg)