Do Hormonal IUDs Raise Your Risk of Cancer? Understanding the Latest Research and the Need for Better Hormonal Options

A new JAMA study links hormonal IUDs to a slightly increased risk of breast cancer, sparking widespread concern. But how big is this risk, and what does it mean for you? This article breaks down the s

A new JAMA study has raised concerns about the potential link between hormonal IUDs and an increased risk of breast cancer. Headlines are warning millions of women who use these devices, leading to worry, confusion, and even panic. So, what does this really mean for you, and how big is the risk?

The focus here is levonorgestrel—a synthetic progestin that's structurally different from the natural hormones our bodies produce. I've always advocated for progesterone-based contraceptives for my patients, especially IUDs when they're the right fit. Not only do they prevent pregnancy, but they can also significantly reduce menstrual bleeding and cramping, making life a lot easier for many women. So, when headlines started buzzing with warnings like "Birth control device may increase cancer risk," I wanted to take a closer look at the science behind these claims.

Today, I want to dive into whether these fears are warranted, what this means for millions of women on any type of hormonal birth control (including "the pill"), and how the lack of better research has left us all with fewer choices than we deserve.

What's Behind the Scary Headlines?

Let's get into the recent study that's been causing such a stir. Published in JAMA on October 16, 2024, the research followed nearly 79,000 women who had recently started using the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) (Mørch et al., 2024). It found that these women had a 40% increased risk of breast cancer compared to those who didn't use any hormonal contraceptives. Over an average follow-up of almost seven years, this worked out to about 14 additional breast cancer cases per 10,000 users for women using hormonal IUDs for 0 to 5 years, with the risk increasing the longer the IUD was used.

These findings are in line with other research showing a small increase in breast cancer risk for women using hormonal contraception, including oral contraceptive pills. The key takeaway? Any form of hormonal contraception that uses synthetic progestins—like levonorgestrel—may slightly increase your risk of breast cancer. But let's put these numbers in context.

A 40% increase can sound alarming, but breaking it down helps. The baseline risk of breast cancer for younger women is quite low, so while hormonal IUD users do face a higher risk, the absolute increase in cases is still small. For an individual woman, the added risk is limited, especially when you weigh it against the benefits of effective contraception. It's normal to feel overwhelmed by statistics like these—risk can be confusing. But understanding both relative and absolute risk is crucial to making informed decisions about your health.

The Real Issue: Synthetic Progestins

So, why is there an increased breast cancer risk linked to hormonal contraceptives? It comes down to the synthetic progestins they contain. Synthetic progestins, like levonorgestrel, are designed to mimic natural progesterone, but they're not identical. They've been chemically modified to be more stable and effective at preventing pregnancy, but these modifications can change how they interact with your body—especially breast tissue.

Research consistently shows that synthetic progestins are linked to a higher risk of breast cancer compared to natural or bioidentical (non-synthetic) progestins. For instance, a population-based study found that synthetic progestins in hormone therapy were associated with a significant increase in breast cancer risk (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.22-1.35), while micronized progesterone did not show a similar increase (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.55-1.79) (Abenhaim et al., 2022). Another large cohort study from the E3N-EPIC cohort also showed that hormone replacement therapy (HRT) containing synthetic progestins was associated with a higher breast cancer risk (RR 1.4, 95% CI 1.2-1.7) compared to HRT containing micronized progesterone (RR 0.9, 95% CI 0.7-1.2) (Fournier et al., 2005).

A systematic review and meta-analysis also highlighted this difference, showing that natural progesterone, when combined with estrogen, was linked to a lower breast cancer risk compared to synthetic progestins (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.55-0.81) (Asi et al., 2016). All of this evidence points to the conclusion that synthetic progestins are largely responsible for the increased breast cancer risk seen with hormonal therapies.

Adding to the evidence, a study published in EMBO Molecular Medicine explored how different synthetic progestins impact breast tissue (Shamseddin et al., 2021). Researchers found that testosterone-related progestins, like levonorgestrel, promoted breast epithelial cell proliferation, which could increase breast cancer risk. These progestins stimulated the expression of RANKL, a key mediator of cell growth in breast tissue. On the other hand, progestins with anti-androgenic properties, like chlormadinone and cyproterone acetate, didn't have the same proliferative effects. This suggests that the androgenic properties of some synthetic progestins are what make them more concerning for breast cancer risk.

This difference matters. Synthetic progestins can stimulate breast cells in ways that natural, bioidentical progesterone might not. That's why synthetic progestins have been linked to an increased risk of breast cancer, and it's also why we need better contraceptive options.

Pregnancy and Breast Cancer Risk: A Complicated Story

To make things even more complex, pregnancy and childbirth also affect breast cancer risk in some surprising ways. In the short term, pregnancy actually increases the risk of breast cancer, especially within the first 5 to 10 years postpartum. This temporary increase is more pronounced in women who have their first child at an older age or those with a family history of breast cancer (Nichols et al., 2019; Blumenfeld et al., 2020; Borges et al., 2020).

A pooled analysis of 15 prospective studies found that the risk of breast cancer peaks about five years after childbirth (HR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.63 to 1.99) before starting to decline (Nichols et al., 2019). This short-term risk is thought to be linked to estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer. In the long run, however, pregnancy actually becomes protective. The same analysis showed that about 24 years after childbirth, the risk drops to below that of women who have never had children, with an HR of 0.77 (95% CI, 0.67 to 0.88) after 34 years. This long-term protective effect is likely due to changes in breast tissue that occur during pregnancy (Nichols et al., 2019; Migliavacca Zucchetti et al., 2020; Fu et al., 2024).

Breastfeeding doesn't significantly change these overall patterns, but some studies suggest it could offer additional protection against breast cancer (Nichols et al., 2019; Borges et al., 2020).

In short, pregnancy may initially increase the risk of breast cancer, particularly in the first decade after giving birth, but it ultimately offers a long-term protective effect. This just shows how complex the relationship between hormones and breast tissue really is, and why decisions around reproductive health are rarely simple.

Why Aren't Bioidentical Hormones an Option?

Here's where the missed opportunity comes in: bioidentical progesterone. Unlike synthetic progestins, bioidentical progesterone has the exact same molecular structure as the progesterone your body naturally makes. This means it could have a different—and potentially safer—effect on breast tissue. But, unfortunately, bioidentical hormones haven't been developed or approved for use in any form of contraception. Why not? It comes down to gaps in research, development, and funding priorities. Basically, another injustice toward women.

Bioidentical hormones are already available for other uses, like hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and they've shown promise in providing a more natural balance with fewer side effects compared to synthetic hormones. But when it comes to contraception, bioidentical options have been largely ignored. It's a travesty that women are left with limited choices—often forced to pick between effective contraception and the potential increased risks that come with synthetic progestins.

Imagine if we had bioidentical contraceptives—a reliable birth control option without the same concerns about increased cancer risk. Investing in bioidentical contraceptive research could make that a reality. It would be a game-changer for millions of women who want to take control of their reproductive health without worrying about long-term consequences. It's time we demand more for women's health—because "good enough" isn't good enough anymore.

How to Make the Right Choice for You

If you're currently using a hormonal IUD or thinking about getting one, it's completely normal to feel both reassured and a bit worried. Hormonal IUDs are incredibly effective at preventing pregnancy, and for many women, they can be life-changing—turning heavy, painful periods into something much more manageable. But the potential for even a slightly increased risk of breast cancer is something to take seriously—especially if you have other risk factors, like a family history of breast cancer.

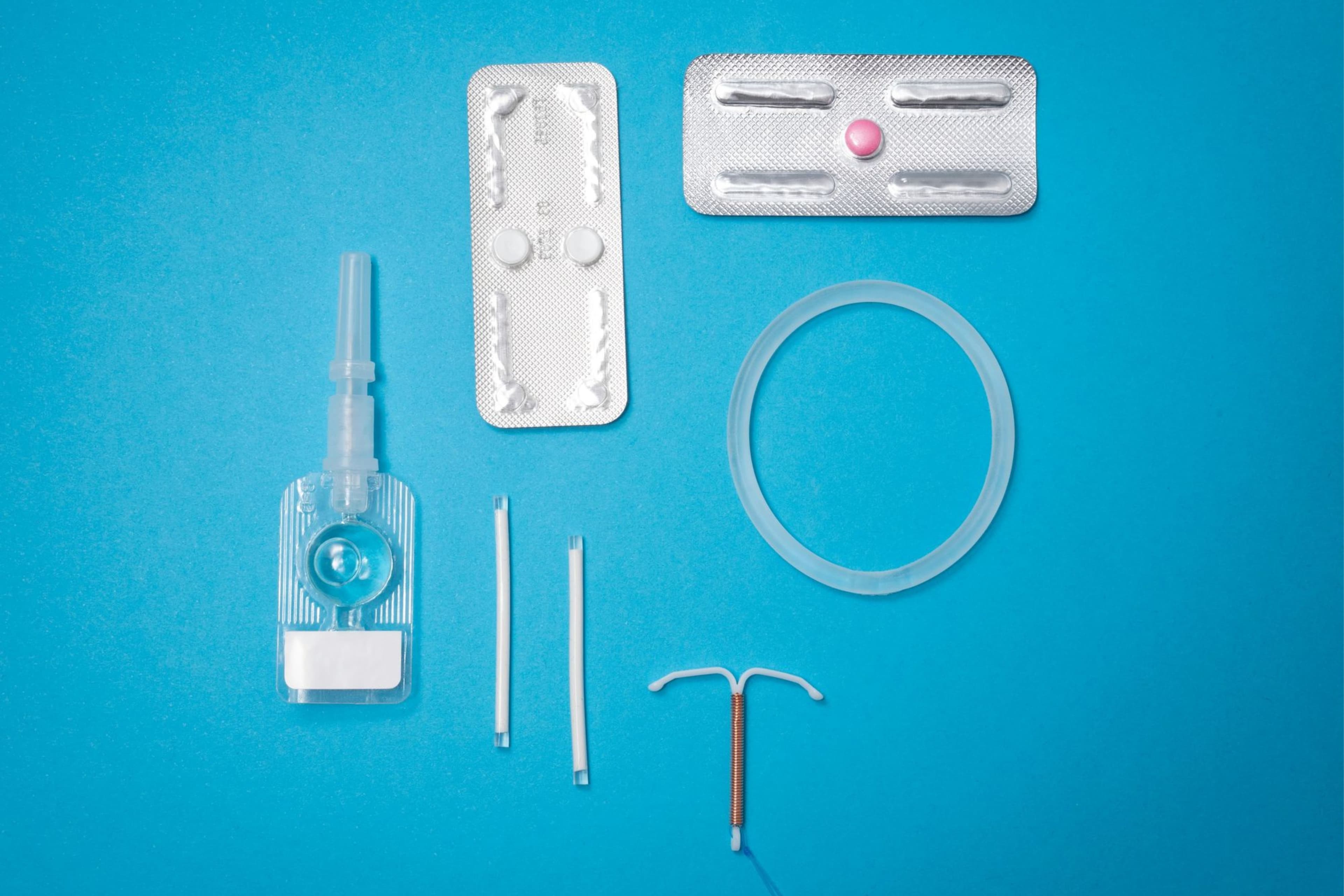

There are also non-hormonal options available, like the copper IUD, which provides effective contraception without using synthetic hormones. This means there's no increased risk of breast cancer associated with its use. If you're concerned about hormone-related risks, it's okay to feel that way. It might be worth discussing non-hormonal methods with your healthcare provider to see if they could work for you.

Ultimately, choosing the right contraceptive method is an incredibly personal decision. It's about more than just preventing unintended pregnancies—it's about your health, your peace of mind, and what feels right for you. Talk to your healthcare provider about your options, and don't hesitate to ask all the questions you need to feel confident in your choice. Your health journey is yours, and you deserve to make these decisions with full knowledge and support.

Wrapping It Up: What You Need to Know

The new study linking hormonal IUDs to an increased risk of breast cancer is a reminder that all medications come with trade-offs. The risk is real, but it's also small—especially compared to the benefits that hormonal IUDs provide for many women. For those looking for innovative alternatives, it's time we start demanding more research into safer options, including bioidentical hormone-based contraception.

Women deserve better choices. Investing in contraceptive research that prioritizes safety and effectiveness can help close the gap and give women the power to make informed, confident decisions about their reproductive health.

If you found this article helpful, consider sharing it to spread awareness. And subscribe to my blog for more on health and longevity.

References

Mørch LS, Meaidi A, Corn G, et al. (2024). Breast Cancer in Users of Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine Systems. JAMA. Published online October 16, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.18575.

Abenhaim HA, Suissa S, Azoulay L, et al. (2022). Menopausal Hormone Therapy Formulation and Breast Cancer Risk. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 139(6), 1103-1110. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004723.

Fournier A, Berrino F, Riboli E, Avenel V, Clavel-Chapelon F. (2005). Breast Cancer Risk in Relation to Different Types of Hormone Replacement Therapy in the E3N-EPIC Cohort. International Journal of Cancer, 114(3), 448-454. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.20710.

Asi N, Mohammed K, Haydour Q, et al. (2016). Progesterone vs. Synthetic Progestins and the Risk of Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0294-5.

Shamseddin M, De Martino F, Constantin C, et al. (2021). Contraceptive Progestins with Androgenic Properties Stimulate Breast Epithelial Cell Proliferation. EMBO Molecular Medicine, 13(7), e14314. https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.202114314.

Nichols HB, Schoemaker MJ, Cai J, et al. (2019). Breast Cancer Risk After Recent Childbirth: A Pooled Analysis of 15 Prospective Studies. Annals of Internal Medicine, 170(1), 22-30. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-1323.

Blumenfeld Z, Gleicher N, Adashi EY. (2020). Transiently Increased Risk of Breast Cancer After Childbirth. Human Reproduction, 35(6), 1253-1255. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deaa102.

Borges VF, Lyons TR, Germain D, Schedin P. (2020). Postpartum Involution and Cancer. Cancer Research, 80(9), 1790-1798. https://doi.org/10.1158/

Until next time - Cheers to your health!

Hillary Lin, MD